Source: guardian.co.uk

Source: guardian.co.uk

We live in the suburbs of the Ugandan capital, and have been together for 10 years. And we are gay. He is a man. I am a man. We are both Ugandans, living, working in Uganda. So, how is it to be gay, and Ugandan, today? We live in interesting times and we have lived a kind of terrifying history.

When we met and moved in together, I was living with my brother. I sat him down and told him: "You know I am gay. I am going to have my lover move in with me." He nodded. I told him that he had the option of living with his dad, if he objected, but I was determined to stay with my lover.

I was simply tired of the hiding, the subterfuge, the lies. My brother did know that I was gay, since we lived in the same house. But not the rest of my family, and not the neighbours. That could not happen.

So, 10 years ago I got a "room-mate" who coincidentally shared the bed with me. We were deeply closeted at the beginning. We thought (hoped, prayed) that nobody knew. After all, though we are grown men living together, sharing a house in Kampala is no big deal. I mean, in Kampala, in Uganda, with the depressed economic conditions, what was more notable was that there were only three of us in the house rather than 10.

I was involved in gay rights issues – some very early, nascent activities. Self-confidence, independence of income and some education helped me, as did a sense of growing anger at my world of duplicity, shame and enforced lies. My partner was more cautious. Not all the things that I did were below the radar, or underground.

It was at his insistence that I made my Gay Uganda blog as anonymous as possible. His was always the voice of caution: wait, don't do that, don't expose yourself, remember that it is no longer you alone.

And, he was correct. I did heed his voice. Because, for a gay Ugandan, life is not safe. Being known to be gay is tough. It is a life of reckless fear, not courage. We do what we do, not because we can, but because there is no other option. From the very first inkling of our sexuality, we learn to hide. And we do hide.

In fact, we gay Ugandans hide so well, and are gracefully camouflaged, that fellow Ugandans frequently ask themselves who the "evil gays" are. Of course, we are their kin. But they don't believe their brothers, sisters, cousins, relatives can be the "evil gays".

In the beginning, I think it was the religious questions that led to my activism. I was baptised into an Anglican family. While in high school, round about the time that I realised my sexuality, I became an evangelical Christian.

But being gay in Uganda and Christian is a real challenge. Ugandans are highly religious and, coming out to myself later, I knew I couldn't reconcile my faith and sexuality. I decided to repudiate faith. But then I went further and became angry at the faith as shown in Uganda. And why not?

The words and actions of our religious leaders are full of hate. Mufti Mubajje, titular head of Muslims in Uganda, believes that all gay Ugandans should be marooned on an island in Lake Victoria. We would then die out and solve the country's gay problem.

When we came out at a press conference in 2007, all the sermons in churches and mosques over the following days were about the evil of homosexuality. An anti-gay demonstration was organised, ultimately limited to a rally at Kyadondo rugby ground. And, there, ministers – both political and religious – railed at the evil homosexuals who had dared to show their faces (even though we were wearing masks).

It was a tough time. I remember, we were home that evening, with some gay friends – kuchus, as we call ourselves. They were a bit worried, because I had been at the press conference and the radio was talking about the imminent arrests of gay men.

That was when my dad revealed his knowledge. He came to our door, anxious. He had heard a rumour that we were all going to be arrested. "Who is going to be arrested?" I asked him, shocked, more by the fact that he knew, than that he was warning me. "You," he indicated towards me and my partner.

Fortunately, the rumours of arrest were unfounded. But, we had been exposed and the exposure was going to grow. Now that gay Ugandans had "come out", we were the target of any newspaper seeking to make a quick buck. I was known. My partner was known.

The anti-homosexuality bill of 2009 further flushed us out of our closets. We found ourselves targeted by a truly horrible piece of legislation, seeking to kill and imprison us for life, all in the name of "family and cultural values". We had to fight, and we had to come out of the shadows to fight.

Death and life imprisonment. No access to information or help. The danger of being reported to "relevant authorities" by pastors, doctors, parents. Mandatory HIV tests. All these are provisions of the Bahati bill. We had to show our faces. We had to, and we did.

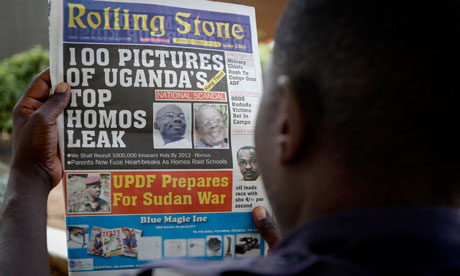

But, though the international outcry enabled the government to go slow on the bill, our exposure was not reversible. Now a tabloid has published the photographs of alleged gay Ugandans, under the headline "Hang Them".

No, it is not easy to be gay and Ugandan. Whether it is denial of HIV prevention services for gay men, or the need to bribe police when you are reported, it is not easy.

Such is the strength of the human spirit: we are gay, Ugandan, and we live and work in the country. Life is tough. But, I dare say, having come through the fire, we are as tough, if not tougher.

Join our page

Join our page

0 comments:

Post a Comment