Image via Wikipedia

Image via WikipediaBy Jacob Papini

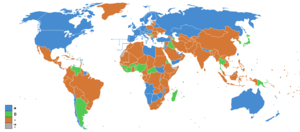

Sovereignty and the nation state appear to be threatened, both literally and metaphorically, as Europe’s permeable southern borders are constantly breached by refugees and migrants entering “illegally”.

In this context it is hardly surprising that the search for a common Immigration and Asylum Policy within the EU, envisaged under the treaty of Amsterdam in 1997, has remained one of the last and most intractable of the measures for harmonising Europe.

Government asylum and immigration policies, notably across Europe, generate contradictory and conflicting political interpretations of the labels “immigrant and refugee”. As a consequence apparently competing, conflicting, contradictory proposals and projects are put on the table aiming at contrasting irregular immigration and refugee/asylum seekers flows. These differences have been assisted in recent years, through the emergence of a “New EU Asylum Paradigm”, showing a convergence of thinking among EU, UNHCR and member States. The principle of “externalisation of refugee processing and protection” (cooperation schemes aiming at strengthening protection capacity in regions of origins) represents a common logic that underpins all actors’ different proposals and policy interventions.

Furthermore, the dominance on the political discourse of the refugee/asylum seeker problematique on one hand and of illegal immigration on the other have tended to obscure the much larger challenge of international labour migration in an era of economic globalisation in demographically aging Europe. Existing official policies in the EU target the highly skilled immigrants, while less skilled workers are admitted in very limited numbers, on a temporary basis and for specific sectors only. Thus there is every reason to think that much labour demand will continue to be met by undocumented workers. Governments tacitly use asylum and undocumented migration as a way of meeting market labour needs, without publicly admitting the need for unskilled migration and a cheap labour force. This reinforces de facto the national political taboos and vulnerabilities.

New proposals have been introduced since the recommendations made by the Treaty of Amsterdam. This provided that, in order to progressively establish an area of freedom, security and justice, the Council should adopt measures on the free movement of persons, together with related measures on external border control, asylum and immigration.

The Stockholm Programme (2010 – 2015) is without any doubt the first step towards the adoption of a concerted Immigration and Asylum Policy within Europe. It represents the new 5-year EU programme for Justice and Home Affairs, agreed by the European Council in December 2009. There are many hopes that it could override institutional infighting and jurisdiction questions that have always slowed progress towards this common goal. Current cooperation between member states on immigration issues, where their differing priorities will not even allow consensus on the issue of labour migration, is poor.

The challenge for the Stockholm Programme will be to be more than box-ticking with little real impact. Stockholm is recognised as a necessary, but insufficient framework for future immigration policy planning. However, the fact that member states will often only take action for short term political gains and that some of those members (UK, Denmark) are uninterested in a collaborative migration policy makes a positive outlook difficult, leaving quick fixes and interim measures the only strategy on the ground. This is exacerbated by economic uncertainty.

In particular the Programme introduces, under the commitment to “a common area of protection”, the principle of burden sharing among member States for hosting and integrating refugees and common processing of asylum applications. The same principle applies between member and non-member countries faced with major inflows of refugees, in order to contrast illegal immigration at source through practical cooperation with third countries. This seems to result in the achievement of an effective and sustainable return policy to be agreed with countries of origin and transit and in the adoption of a new asylum paradigm based on the externalisation of refugee processing and protection.

The goal is the creation of mechanisms in regions of origin that remove the necessity for people in need of protection to come to Europe by creating procedures and infrastructures that enable the countries in the region of origin to offer effective protection. The Amnesty International EU office report on the Stockholm Programme gives more details about the provisions on immigration and asylum.

The impression is that the new approach introduced with the Stockholm Programme seems to be less about protecting vulnerable people than ensuring that people can be legitimately returned to their regions of origin. This raises concerns about the abandonment of the “principle of non refoulement” and serving de facto the purposes of EU states to drastically reduce immigrant and potential refugee flows.

Furthermore, it may take years for the Stockholm Programme to be effectively adopted and implemented, leaving room for EU states to develop bilateral initiatives in clear contravention of the principles of the 1951 Convention, the Declaration on HR and EU Returns Directive on immigrants rights.

The Programme also addresses immigration under the commitments to develop “effective policies to combat illegal immigration”. Despite setting out a clear objective in achieving the development of a forward looking and comprehensive European migration policy, the Stockholm Programme is still focusing too much on illegality, rather than the more difficult question of providing access to European shores for labour migrants and asylum seekers. A more holistic approach should also assert the need to embed rights and citizenship in the thinking and policy on immigration, and simultaneously distance it from the security agenda. The same approach could create a positive links between migration and development, to be considered respectively in immigration policy and foreign policy.

The harmonisation process seems to be a very long one and the first attempts seem to lack of coherence, cooperation and courage. The EU should put in place a solid legal framework of protection that is in compliance with international refugee and HR law and standards, if the real goal is to override the impasse represented by bilateralism and single state priorities.

Another reflection should stress the fact that the Programme has been thought and developed as a Eurocentric one, and the global south prospective and constraints seem not to have been considered. It raises the question of whether it remains productive to analyse the policy and practice of immigration and asylum in the north without reference to wider debates about migration in a globalised world.

Jacob Papini graduated in Development Economics from The University of Florence in Italy in 2005. Since then he has worked as Project Co-ordinaor for the INGO COSPE in Ghana on a four years EU project “Small and Micro Enterprises System” and for the University of Florence Dep. of Statistics and Economics as field researcher on “Informal Economy in Ghana”. He undertook a Postgraduate Course at LSE in Democracy Building and he is now a MSc student of Conflict, Migration and Development at SOAS.

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=c325c4f4-e254-4624-ad5a-d4f69114f879)

Join our page

Join our page

0 comments:

Post a Comment